What is Poetry to an LLM? Reflections from an Annotator

What is poetry? That seemingly straightforward question motivates the collection of phonetical, prosodic, historical, grammatical, and other texts in the Princeton Prosody Archive and formed the basis for a project that I undertook with other interns over the summer and fall of 2024. We were tasked with identifying and annotating quoted excerpts of poetry in the PPA to create a ground truth dataset that could be used for evaluating or fine-tuning methods of automatic poetry detection, including Large Language Models (LLMs). In line with the PPA’s rethinking the conceptualization of large amounts of data on different aspects of prosody, including what a poem is, a fundamental aspect of this task involved rethinking my assumptions about the definition of “poetry.”

In addition to discussing how this task led me to reengage with how I understand “poetry,” the task of identifying poetic texts and curating data for an LLM raised the intriguing question of whether there is an analytical component to the “rote” work of annotation. In the context of the rise of LLMs, the vast amount of data needed to train AI models frequently relies on human workers completing repetitive tasks, as in Amazon Mechanical Turk. While this poetry annotation task may appear similarly rote at first, my experience demonstrated to me that these works of data curation, particularly in an academic research context, can be deliberative and engaging, even across varying levels of complexity.

To explore the two threads of what a poem is and the effortful nature of applying this definition to the annotation task, this essay will traverse 1. how “poetry” was defined in this task, 2. the methodology of annotating poetry according to that definition, and 3. the challenges that arose throughout the process. In doing so, I find that annotating these poems was an intellectual task, and an intriguing one!

Defining: what is poetry?

The Oxford English Dictionary primarily defines a poem as “A piece of writing or an oral composition, often characterized by a metrical structure, in which the expression of feelings, ideas, etc., is typically given intensity or flavour by distinctive diction, rhythm, imagery, etc.; a composition in poetry or verse.”[1] This definition provides a broad means by which to distinguish poetry — by its use of literary mechanisms to elevate ideas or feelings of a written or oral text. The OED’s definition would seem to encompass familiar forms of poetry — ballad, haiku, lyric poetry, free verse, and so on — that are often visually evident on the page by virtue of line length and enjambment. In our annotation task, though, we needed an even more inclusive definition.

For the project, “poetry,” “poem,” or “poetic text” were functionally defined in our annotation handbook through the following criteria, but also “not limited to” them:

- rhythmical, metrical, or stanzaic writing;

- writing organized into verse lines, which may be rhymed or unrhymed;

- plays or dramatic works written in verse;

- popular forms such as nursery rhymes, songs, and marches;

- biblical verse such as hymns, psalms, and prayers;

- and translations of such writing

In addition to the above information, our annotation handbook noted that this poetry could “be in any language or system of writing, including phonetic script” and could be historically recognized as poetry or “unknown or invented writing that displays the characteristics of poetry,” as well as “sayings, idioms, maxims, aphorisms, and proverbs, depending on the context and provenance.”

I was particularly struck that our annotations could include works not already historically distinguished as poems, such as “unknown or invented” poems. What I moreover noticed going into this task was its inclusion of different forms I hadn’t thought of, such as sayings or marches. Again, what was poetry? I had previously considered some songs to be “poetic,” for example, but had categorized them separately. How could a song be a poem? What grounds the separation of forms and how could categories engage with one another? Going into the annotation process, these questions fueled my reconsideration of how I understood poetry, or even attempted to define it strictly at all. The OED dictionary definition reflected the notion of poetry as a form that most fundamentally includes certain literary mechanisms to express emotions and ideas, which became more fluid during the annotation process.

Methodology: analyzing poetry

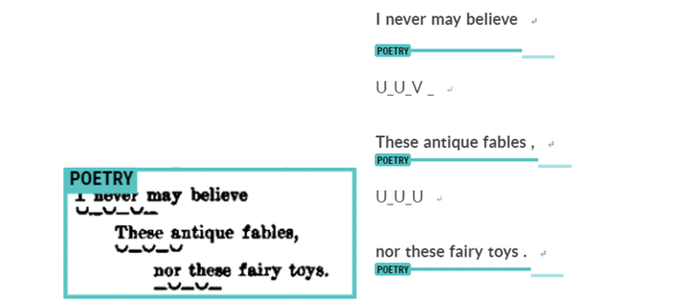

To annotate the poetic excerpts, we used a platform called Prodigy to construct a dataset of poetry spans. The interface showed an image of a page alongside an Optical Character Recognition (OCR) transcription of the text, as demonstrated in the image below of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “Break, Break, Break” (1842).

Kaluza, Max. A short history of English versification, from the earliest times to the present day, p. 284. https://prosody.princeton.edu/archive/mdp.39015010540071/

The annotation involved both manually drawing a box around the poem on the page image and selecting the corresponding OCR text, specifically excluding surrounding punctuation that was not a part of the poem, OCR renderings of prosodic marks (as depicted below), or extraneous information including citations or titles. So, the annotation dataset would include just the poetic OCR text itself and the visual representation of it.

Scott, John Hubert. Rhythmic verse, p. 82. https://prosody.princeton.edu/archive/mdp.39015010540071/

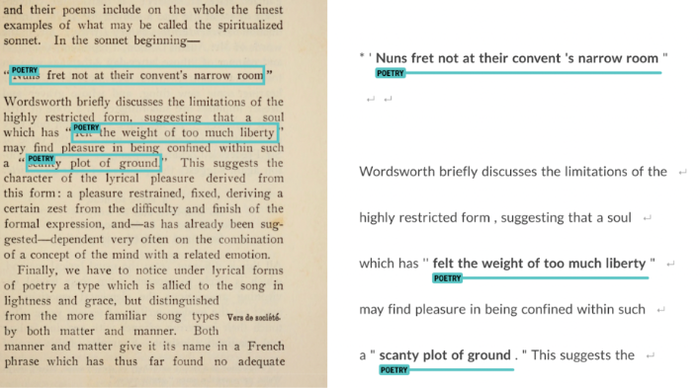

To identify this text, as shown above, in many cases there were visual clues to identify poetry — like by whitespace and form. In other cases, poems appeared as quoted single lines within text or in prose form, as demonstrated below.

Alden, Raymond Macdonald, An introduction to poetry, p. 71. https://prosody.princeton.edu/archive/dul1.ark:/13960/t5w67998k/

This act of transforming poetry into data for the LLM furthered my engagement with poetry as a form. While the poetry excerpts on the page images were often visually stanzaic, this was not always the case — when poems were quoted within a line of prose, I had to use context clues, such as title or author, to identify the quotation as poetry. In these cases, I began to wonder, when the line of an idiom, a song, or a historically recognized poetic text is extracted from its context, could an LLM distinguish it as poetry?

To render poetry into the decontextualized data of spans and boxes as an annotator, I relied variously on noticing traditional poetic features, such as meter, stanza, and rhyme, as well as a poem’s content and surrounding paratextual information in paragraphs. As a result, my understanding of “poetry” expanded even more through the different challenges of annotating ambiguous quotes.

Challenges: Songs, drama, and quotes without context

Principally, annotating the poetry spans involved different technical challenges, such as how to exclude prosodic marks or extraneous information within the text spans. Other issues included OCR transcriptions that were inaccurate due to poor scan quality, or pages that were cut off on the margins. The most informative challenges, though, I found to be the cases where I struggled to determine whether or not texts were “poetic.”

One key example was song. While there were cases where poetic lines appeared next to musical notation to demonstrate a poem’s meter, there were also instances of sheet music for song, as depicted in the example below that I also recognized and annotated as poetry. Besides the challenge of identifying these excerpts as poems, a technical difficulty was the visual and textual annotation of these songs.

Bolenius, Emma Miller. Teaching literature in the grammar grades and high school. https://prosody.princeton.edu/archive/ien.35556038200176/

In the example of the folk song above, two lines of lyrics are visually and thus textually grouped on the OCR transcription. However, in other cases, lines were more interspersed, which involved more annotations of a single song and having to exclude multiple interruptive musical notes or marks.

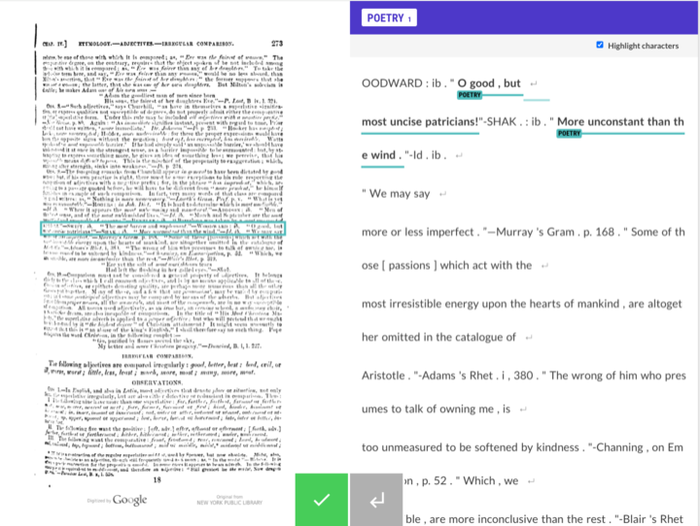

In addition to song, dramatic excerpts posed another challenge, as some drama was written in prose, others in verse. Annotating these excerpts principally involved identifying rhythmic patterns as well as line breaks or researching the line to identify the source and determine whether or not a dramatic excerpt was verse. Two examples of dramatic verse – excerpts from Shakespeare’s Coriolanus and Romeo and Juliet respectively – are depicted below.

Brown, Goold. The grammar of English grammars, p. 286. https://prosody.princeton.edu/archive/wu.89099427403/

The most challenging excerpts, though, were quotes within prose that did not have contextualizing information like author or title to draw on. While I was able to research some to obtain their paratextual information identifying the form or author, others did not appear in return searches, like the first example below.

Blair, Hugh. Essays on rhetoric, p. 101. https://prosody.princeton.edu/archive/CB0131168216/

As a result, I had to judge what was poetry based only upon the nature of the text itself, again looking for rhythm, rhyme, meter, alliteration, imagery, other poetic qualities within a line, and occasionally extraneous information such as additional quotes or analyses of them.

Ultimately, what I incorporated was to err on the side of including text, in line with the expansive notion of what poetry is. Throughout my annotations, I found myself returning to the question of the purpose of this data, and how the LLM would utilize it. I would ask myself; how does this excerpt contribute to an understanding of “poetry”? What about the form does it represent? Overall, this resulted in more inclusions of “poetic text.”

Conclusion: An intellectual task?

When I now conceptualize “poetry” I consider and understand it more expansively than before this project. I also respect the distinctiveness of forms of art – like song in its musical interactions in performance and different cultural contexts. I found it important to remember the fluidity but also uniqueness of different forms, poems, texts, orations, and authors' experiences, each engaging with different literary traditions, styles, cultures, and worldviews. Ultimately, also taking this into account, it feels restrictive to label or define exactly how I perceive poetry in the context of the contents of this essay. Still, my understanding of poetry has expanded such that I identify and see value in considering increasingly more texts poetry. Throughout this project, my takeaway has been to embrace how the form, as I viewed it traditionally, can also apply to song or drama, and challenge my own understandings of literary history.

Returning to the question of providing annotation data for LLMs, the necessity of applying critical thinking skills in various ways to determine what constituted a poem — observing visual form, taking into account extraneous information, researching the text, analyzing the language — solidified the intellectual nature of this task for me. The task involved critically evaluating pieces of evidence, applying my understanding and changing understanding of poetry, and coming to a conclusion about what to include in the dataset. In the wider context of curating datasets for LLMs, while the nature of and level of engagement with annotation may vary for different projects and tasks, my experience taught me the necessity for human curation of these datasets, and that the project itself was a transformative learning experience.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Mary Naydan for helping direct the topic of this essay, finding many illuminating examples from Prodigy for this analysis, and for her editing suggestions. I would also like to thank Anna Konvicka for the thoughtful assistance and directions throughout this project, along with Meredith Martin, Wouter Haverals, and Laure Thompson. Lastly, I thank co-interns Anthony Nathan and Molly Taylor for their meaningful contributions to the poetry annotations!

- Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “poem, n., 1.,” last modified December 2024, OED Online.