Exploring Poetry in All Its Forms: Annotating Works from the Princeton Prosody Archive

The Princeton Prosody Archive is a digital collection of English-language works about poetry and prosody written between the sixteenth and early twentieth centuries. This archive provides an extensive collection of texts that illustrate the evolution of poetic forms, styles, and conventions over time. It serves as a valuable resource for researchers studying themes of language, rhythm, and meaning in poetry. By offering access to digitized versions of these texts, the archive makes it possible to explore historical and literary developments in a systematic and comprehensive manner!

Many of the works in the PPA include excerpts or quotations of poetry to illustrate particular prosodic concepts. But how could we systematically identify when poems appeared on a page? To begin to address this question, I had the opportunity to use Prodigy, an advanced and versatile annotation software tool, as one of three undergraduate annotators. Prodigy’s versatility and user-friendly interface make it a valuable tool for researchers working in the fields of digital humanities, Natural Language Processing, and machine learning.

One of the key features of Prodigy is the ability to create image boxes and to highlight specific spans of text. This allows for the precise annotation of poetry on the page, whether it be single lines, whole stanzas, or particular phrases. While the ultimate goal is to train an AI model to recognize poetry on a digitized page, human annotation is needed to produce ground truth data that can be used for evaluation or fine-tuning.

Through this work, I encountered a wide range of documents containing poetry presented in diverse ways, reflecting the varied practices of poetry publication across different periods, as well as the idiosyncratic citation practices and metrical systems of prosodists.

Some poems were neatly formatted with clear stanza breaks and uniform typefaces, while others featured more fragmented or unconventional layouts, with unusual spacing, inconsistent punctuation, and even musical scores! These intriguing nuances in the presentation of poetry, such as the interplay among form, layout, and textual structure, were particularly engaging. Navigating these complexities with Prodigy posed an interesting challenge, as we had to square the capacities of the tool with the idiosyncrasies of the PPA data and the goals of the task. Yet, working through these challenges was also an opportunity to reflect on how human expertise shapes and refines computational tools, revealing the ways in which scholars and machines can engage in an evolving dialogue.

In this editorial, I’m eager to highlight my journey as an annotator, exploring the fascinating diversity of poetic works in the Princeton Prosody Archive, where each poem brings its own unique twist to the page! I’ll also share some of the interesting encounters I had with PPA texts and the challenges of annotating such varied spans of poetry with Prodigy, navigating everything from irregular formatting to digitization quirks along the way.

Prosodic Marks

As I worked through the texts in the Princeton Prosody Archive, I encountered several poems that included prosodic marks, which are symbols used to indicate rhythm, stress, intonation, and other features of spoken language. These marks, such as vertical bars ("|") separating metrical feet or accent symbols for stress, are often rendered correctly by OCR on the words and letters themselves, but in some instances, these marks appeared on separate lines entirely, disconnected from the actual words they were meant to modify. It was a fascinating experience seeing how OCR rendered often intricate and complex stresses and symbols in a digitized text, sometimes accurately and sometimes not, and the complex “uh oh” moments presented a challenge that we had to navigate, as we’ll see below.

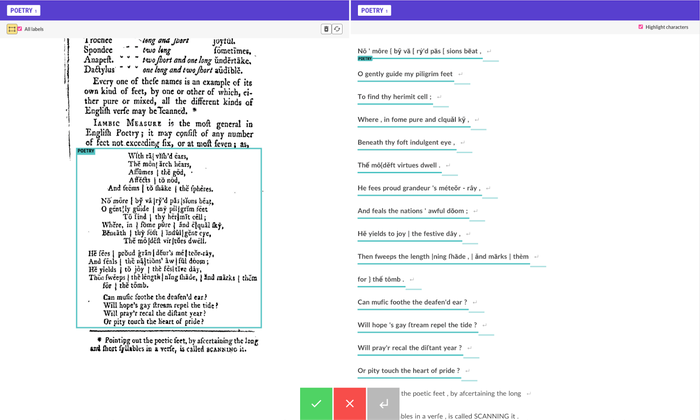

In this example, the prosodic symbols are preserved and rendered mostly accurately, but inconsistently, in the OCR. The vertical bars appear as various symbols, not only as the pipe symbol “ | ” but also square brackets “ [ ” and curly brackets “ { ”. Diacritical marks often appear on top of the letters, as in “méteǒr.”

We decided to include the prosodic marks that were inseparable from the letters, since there was no way to exclude them, even though they weren’t technically part of the poem. However, we decided to exclude marks that appeared on separate lines from the poetic text or were placed inconsistently in the OCR. And then there were the moments when the OCR turned into a jumble of symbols, with prosodic marks misinterpreted as garbled letters and symbols that were nowhere to be found on the page image.

This happened frequently with musical notation, where the system struggled to differentiate between textual elements and musical symbols. It was these quirky errors that added a fun layer of unpredictability to the process, turning simple annotation tasks into little puzzles as we worked to make sense of the distorted text and emphasized the importance of the human touch.

Here, we observe a common error, where the musical score is rendered as text in the OCR, such as “P10PP 196 PIED,” and, intriguingly, even a Korean character (“외”) is mistakenly included.

Typography Changes Through Time

Since the Princeton Prosody Archive spans several centuries of English-language poetry, one encounters a wide range of changes in conventions and typefaces throughout the collection. These shifts reflect the evolving nature of poetic style, printing technology, and literary trends over time. Much of the difficulty in annotating these texts stemmed from the quality of the OCR, which sometimes struggled with historical typefaces or formatting quirks. In our first round of annotation using HathiTrust materials, which primarily contained 19th-century texts, we encountered issues like faded print and irregular spacing, but the texts were largely consistent with modern printing conventions.

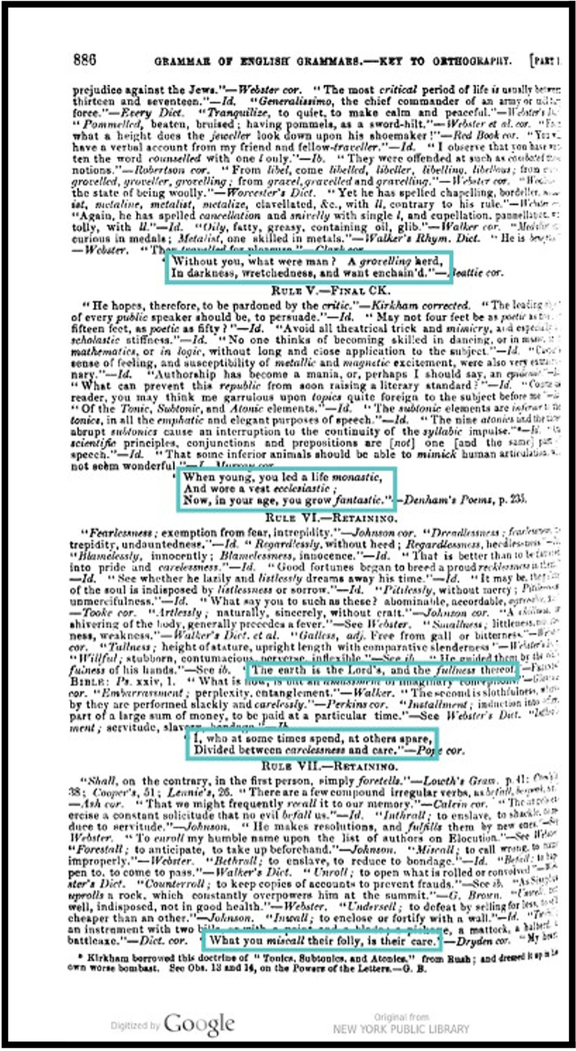

One notable example was Goold Brown’s Grammar of English Grammars (1851). What made annotating this text particularly tricky was the combination of irregular formatting and presentation choices made by the author, which often stumped the OCR and complicated the annotation process. The text features an array of unconventional layouts, with densely packed quotations, varying font sizes, and inconsistent line breaks, all of which contributed to the challenges we faced.

Figure 1, for example, required strong attention to detail since the poetry was stacked between spans of non-poetic text, making it challenging to distinguish which lines needed annotation. This format necessitated a close reading and a discerning eye to ensure that only the relevant poetic lines were selected for annotation, while avoiding the surrounding prose or commentary.

Figure 1: Stacked quotations with both poetic and non-poetic text, requiring careful attention to distinguish which spans needed annotation.

In Figure 2, the slant of the page introduced an additional layer of complexity. The skewed angle of the original text led to the OCR rendering words out of order, which made interpreting the intended structure of the page difficult. We had to reassemble fragmented OCR to recreate a coherent reading of the page.

Figure 2: The slant of the page caused the OCR to render text out of order, complicating the annotation process.

Figure 3 presents yet another obstacle, where the OCR cut off the right-hand side of the text entirely due to the typographical presentation of the page. This left entire phrases or portions of lines missing, meaning we had to simply work with what was given in the OCR, often making the best of incomplete information and navigating the gaps with careful judgment.

Figure 3: The OCR cut off the right-hand side of the text due to the page’s typographical presentation, challenging accurate annotation.

Each of these scenarios required careful judgment and creative problem-solving to navigate successfully. The experience underscored the critical role of human expertise in digital humanities projects, particularly when dealing with historical texts that defy modern formatting conventions.

Moving to the second round of annotations with materials from Gale/Cengage, which focused on 18th-century texts, introduced new and unexpected challenges. Older typographic conventions, such as the long “s” and elaborate ligatures, often confused the OCR and required extra vigilance in annotation. Navigating these complexities meant refining our approach, carefully cross-referencing page images, and adjusting our annotation strategies when we encountered distinct characteristics of earlier texts. It was a constant process of adaptation, accommodating the annotation task to the idiosyncrasies of historical texts.

The medial “s”

As previously mentioned, one fun idiosyncrasy I encountered was the medial "s" (ſ), a character frequently used in texts published prior to the mid-19th century, that often appears similar to the modern “f.” While the sentence above in actuality reads: “Thus at their shady Lodge arriv’d, both,” the OCR would render the word “shady” as “fhady,” an unintelligible word. Despite recent advancements in OCR technology [1], it was interesting to see how traditional typographical conventions like the medial "s" still pose a challenge, requiring extra care to ensure accurate annotation.

Catch Words

Catchwords demonstrate another interesting interpretive decision we had to make regarding what to include or exclude in our annotations. A popular convention with pre-19th century publishing, catchwords are found in the Princeton Prosody Archive works from Eighteenth Century Collections Online. While the catchword may be a part of a poetry span that follows on the next page, for the purposes of our annotation task and training the AI model, such catchwords were not included, as they are more related to the printing process than the actual content of the poem and including them could introduce unnecessary noise into the dataset.

Quirks with Prodigy and Going Back to the Drawing Board

Another challenge I encountered during annotation was related to word tokens and how faults with the OCR influenced the process. Initially, the team decided to highlight whole tokens rather than individual characters to ensure consistency and avoid accidentally leaving stray characters behind. With this approach, the annotation would snap to the full token, even if we stopped highlighting in the middle of a word. However, we soon discovered that this method posed issues when OCR failed to render spaces between words correctly, causing multiple words or extraneous punctuation, such as quotation marks or commas from an author quoting poetry within their work, to be joined into a single token. This led to misleading annotations in which non-poetic elements were mistakenly highlighted as part of the poem.

Because the tokenizer separates words based on whitespace, <heart!”–Thomson> was considered a token, and there was no way to exclude the end quote and subsequent citation.

Recognizing this problem, we revised our guidelines in the second round of annotation and changed a setting to allow for character-level highlighting, allowing for greater precision in distinguishing true poetic text from surrounding noise. This adjustment was a clear example of the human touch in annotation, our ability to recognize and adapt to the idiosyncrasies of historical texts in ways that automated processes alone could not. By refining our approach, we ensured that only the essential elements of the poetry were captured in the ground truth dataset.

Another key challenge we encountered was deciding how best to work with the image annotation boxes. For image annotations, the squares and rectangles we could draw sometimes made it difficult to isolate just the relevant text. As a result, prosodic symbols and other extraneous marks often had to be included alongside the poetic text. In contrast, text span annotations offered much more precision. They allowed us to highlight only the words directly relevant to the poem, leaving out unnecessary elements. This distinction in the level of precision between the two methods was why we chose to use both approaches. Image annotations were helpful for capturing the visual layout of the text, while text span annotations gave us the control needed to focus solely on the poetry itself. By using these two methods, we ensured that we could leverage the merits of each approach and capture the poetry as accurately as possible.

As with any project, there are moments when the team encounters challenges or topics that require deeper discussion. One issue we faced was the frequent reference to Biblical passages in texts discussing prosody. While these passages are often cited as examples of prosodic features, we had to address the fact that the Bible is not primarily written in verse. To ensure consistency in our approach, we collaboratively established a set of guidelines to define what constitutes poetry in this context. After thoughtful discussion, we updated our annotation provisions in the second round, deciding to include specific Biblical forms like hymns, psalms, and prayers, which clearly align with poetic structures. These moments of refinement remind us that flexibility and collaboration are key in the digital humanities. It was through ongoing dialogue and teamwork that we ensured our annotations were both efficient and accurate, adapting to the nuances that arose along the way.

The Evolving World of the Digital Humanities

As a student majoring in economics and minoring in English, this project has been an invaluable opportunity to bridge the gap between technical analysis and literary interpretation. Engaging with the Princeton Prosody Archive using Prodigy allowed me to merge computational tools with humanistic inquiry, deepening my appreciation for how technology can enhance, but not replace, close reading and critical analysis. On the one hand, I developed a deeper understanding of how modern tools, like OCR and Prodigy, can streamline and enhance the process of working with historical texts, while being reminded of the complexity of poetry and how analyzing form, rhythm, and language from texts throughout English history requires nuanced interpretation that technology alone cannot fully capture. For example, OCR often misreads archaic spellings or damaged print, requiring human intervention to correct transcription errors. Prodigy, while useful as an interface for displaying and working with annotated texts, reinforced the importance of human input in refining data and ensuring accuracy in the digitization process.

This project also demonstrated the broader implications of integrating computational tools into humanities research. By working with OCR and Prodigy to organize and annotate texts, I saw firsthand how digital tools can assist in large-scale text analysis, making research more efficient without sacrificing depth. At the same time, I encountered the limitations of these tools, particularly in their inability to interpret meaning or recognize the nuances of poetic structure. This underscored the importance of human oversight in ensuring that technological advancements serve as enhancements rather than replacements in literary scholarship.

Ultimately, this experience broadened my perspective on interdisciplinary research, showing me how technical skills can complement fields beyond their traditional domains. It reinforced the idea that while AI and machine learning offer powerful tools for processing and organizing data, human creativity and critical thinking remain essential for interpretation. More broadly, this project demonstrated how blending quantitative and qualitative approaches can lead to richer, more nuanced insights: an understanding that will continue to shape my academic and professional pursuits.

- The PPA team re-OCR’d Gale’s content using Google Vision prior to beginning the annotation task. This was a significant improvement on Gale’s 2008 ABBYY Finereader OCR in terms of overall quality, but introduced some artifacts such as the rendering of the medial “s” as f.